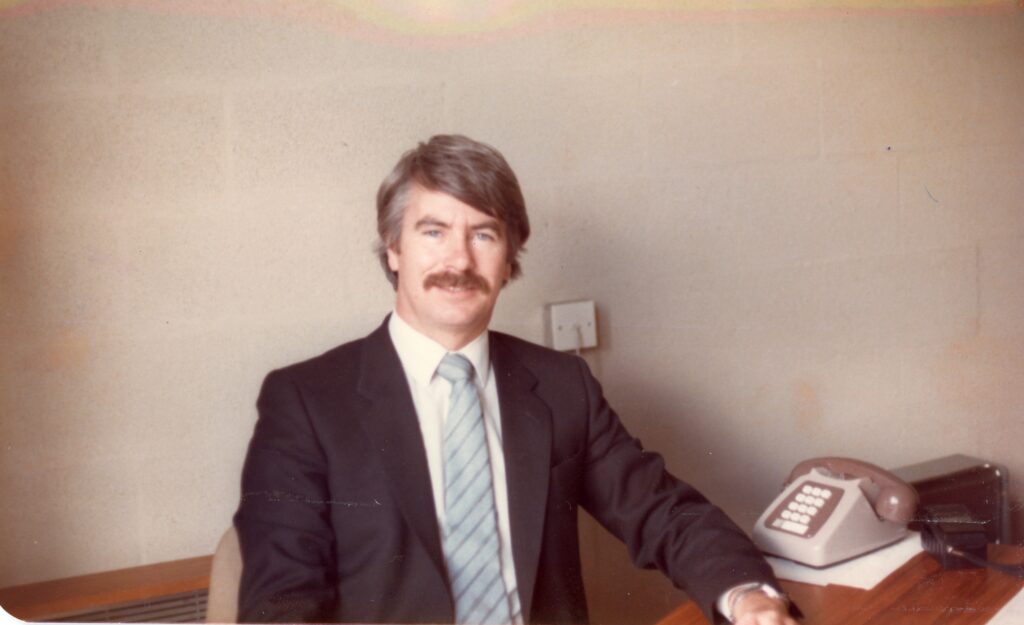

In 1984, Sir Bernard O’Connell was about to start his tenure as Principal at Runshaw. In 2004, the year he retired, he sat down with The Guardian’s Peter Kingston for a catch up…

Bernard O’Connell – or Sir Bernard, as he became in 2004 – grew up the youngest of 13 in an Irish Catholic Liverpudlian family. 20 years ago, The Guardian’s Peter Kingston sat down with the man himself for a catch up.

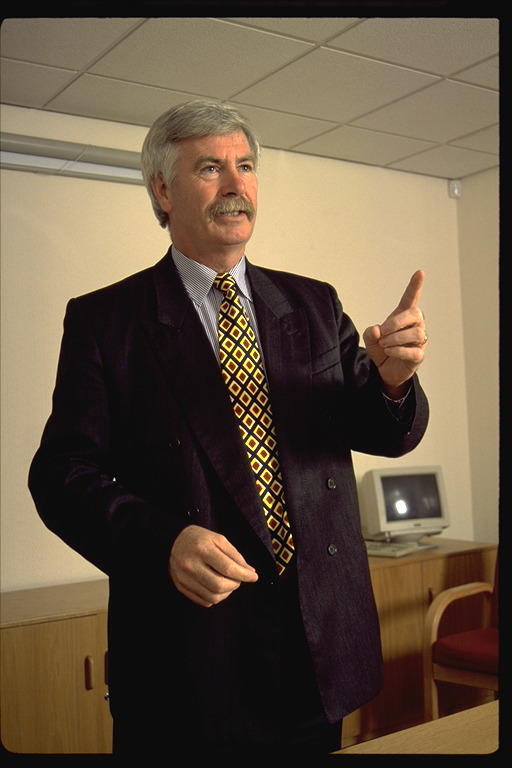

“It really is Runshaw’s success,” says the solidly built, quietly spoken, genial man, with no false modesty. “I’m not famous for anything else. I’m not on any committees. I don’t get out very often. I stay here. My policy – I’m not saying it’s right, by the way – is that I run Runshaw and this is where I should be most of the time.”

Except when he is in his beloved Liverpool. O’Connell tried living near the college when he took up the job, but before a year was out had moved back to Wallasey. On his office wall is a picture of the view over the Mersey from his house, that classic vista of the Liver building and waterfront. The success of the institution that he took over in 1984, after it had changed from sixth-form college to tertiary college, is remarkable by any measure.

Since then, the college, situated on the edge of Leyland, the small Lancashire town once the home of the car manufacturer, has grown to include what he reckons is Britain’s largest sixth-form centre, with 3,550 students.

Of these, the 1,700 doing A Levels consistently rack up a 99% pass rate and a success rate – combining exam achievement and retention – of 84%, matching the top 10% of sixth-form colleges.

“When I came here the results were appalling, with just a 68% pass rate at A Level and a dropout rate of 30-40%. The results from vocational courses and adult education are also very good. In the sixth-form centre, 1,200 students are doing vocational A Levels and BTECs; 600 are doing a range of Entry Level and Level 1 and 2 courses”.

He firmly believes in running a discrete centre for 16 to 19-year-olds. In 1995 adult students at Runshaw were put on a separate site. Now there are 1,000 adults doing university access courses, 1,000 learning basic skills, 700 on “returner” courses, 4,000 part-time students on vocational courses and 300 students pursuing higher education. On a third site, the college runs a thriving business centre offering local employers a large range of short courses. Runshaw flouts the government’s preferences for specialist, niche institutions rather than general FE colleges. “Margaret Hodge, whom I admire, came here to open a building and quoted Runshaw as being the exception to her rule that you couldn’t be all things to all people.”

Success didn’t come quickly. For much of his first decade as Principal, the college chugged along, albeit with a dismal level of funding. O’Connell, who started his career teaching Politics, says he had never been much concerned with management theory. His interest was kick-started by the Education Reform Act in 1990. “It told us to adopt best businesslike practices, but nobody said what these were.” He and his senior managers spent three years trying vainly to discover them. “We made all the mistakes you can imagine. Everything we did was a disaster. We wasted a huge amount of time, energy and goodwill and were worse off than when we started.”

Then, in 1993, the year of incorporation, he decided to carry out a staff survey. For novices, such surveys are invariably a shock. It was a year of rock-bottom morale in further education, when staff were being shoved into new contracts. “When you first do a staff survey in any organisation it’s not usually good news. Ours wasn’t. The survey made me think there was a need for change. I just didn’t know what to do about it.”

He turned to a friend for advice, one of the college governors, who was human resources director for Leyland Trucks. He told him Leyland Trucks had been through a programme of culture change that had increased profits by £10m and effected a “quantum leap” in staff morale. The college hired the company’s consultant and began a major transformation over 18 months. The consultant pointed out that the management had mistakenly been trying to change systems, structures and strategies – the so-called three “hard Ss” – before addressing the four “soft Ss”: staff culture, shared values, management style and skills. Intensive discussions with staff followed. “It was very powerful. The programme was finding out what people thought about the management.”

The consensus reached was that the particular management style desired was a balance of tough (not tolerating shoddy performance) and tender (supporting subordinate staff and showing they were valued). This blend ran counter to the macho management culture in vogue in the sector. Inevitably some managers veered to one or other extreme. For those who couldn’t change, a way was found for them to bow out with dignity. “There were no sackings.” In the process, a clear concept of a Runshaw culture emerged, defining what was expected of staff and students. “Students tell me they are shocked at what they find here, the rigour, our high standards and expectations, but they never complain about it.”

The college borrowed a technique pioneered at Greenhead, the remarkably successful Huddersfield sixth-form college. This sets every new student on their first day a final performance target, such as the grades they are expected to achieve at A Level, and constantly monitors them to ensure they stay on track. “Nothing we do is stuff we’ve invented. We borrow from everywhere.”

O’Connell says the high demands on students are backed up with extensive support and “a big investment in fun”, sports, clubs, societies, music and drama. Runshaw’s success and its larger-than-average classes – 20 compared with a sector average of 11 – have transformed the finances. This has enabled the Principal to cut teaching loads. A Level teachers now do 18 hours a week plus two hours of personal tutoring, instead of 25 hours in the classroom. To ease the burden large classes put on staff, he tried hiring outside help to mark homework. “We started with Maths and used a local A Level examiner. It solved the workload problem and as a bonus he gave valuable feedback about the different styles of teaching that were coming through in the students’ work.” Most subjects now use external markers.

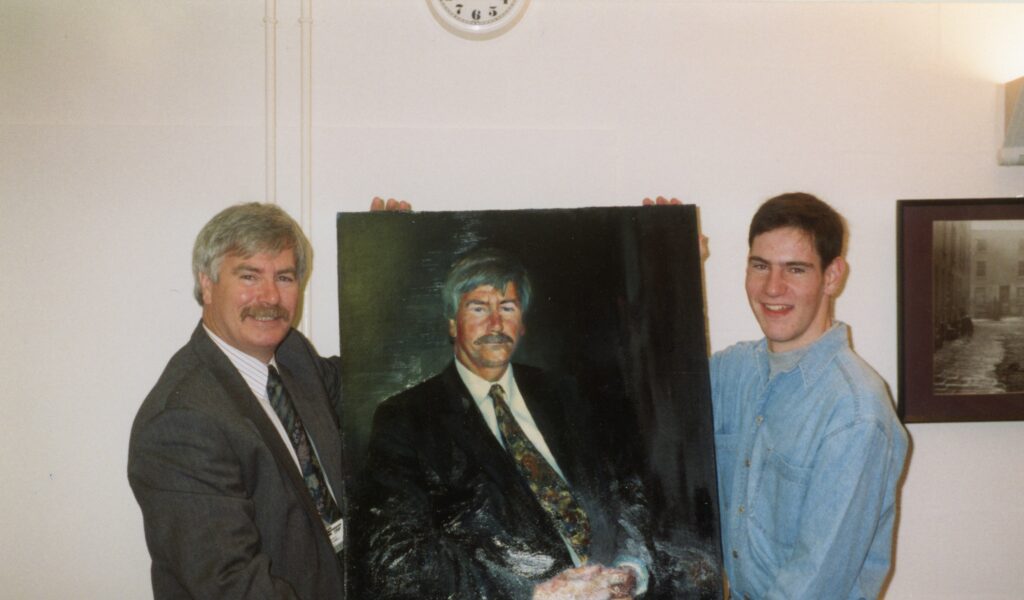

O’Connell also decided to adopt the business excellence model developed by some of Europe’s leading companies in the late 1980s. In 2002, Runshaw’s implementation of the model won it the UK Business Excellence award in the public sector. It then entered the European version of the competition and won. “That may have something to do with the knighthood…”

– Peter Kingston’s interview with Sir Bernard O’Connell, 2004.

And the rest as they say, is history… Bernard’s reign lasted for 20 years. We were privileged to welcome him back to college to celebrate our 50th Anniversary Event. Runshaw wouldn’t be the college it is today without him, and for that, we are all eternally grateful.

For more Alumni content, visit the Alumni section of our website here or follow our Alumni pages on  and

and